Arlington County Genealogy Records, Wills and Estates

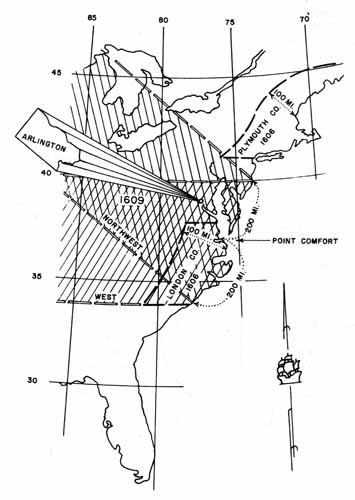

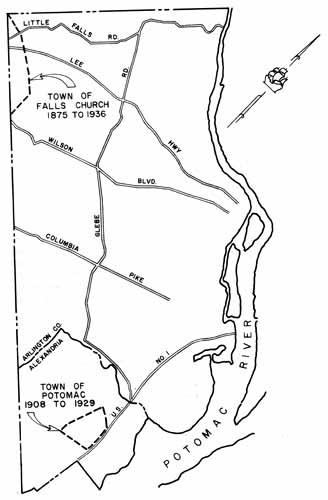

Arlington County was originally part of Fairfax County. One of the original land grants was awarded to Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron. The name of Arlington comes from Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington whose name had been applied to a plantation along the Potomac River which was acquired (in 1802) by George Washington Parke Custis, grandson of First Lady Martha Washington. The estate was eventually passed down to Mary Anna Custis Lee, wife of General Robert E. Lee became Arlington National Cemetery during the War Between the States when the U. S. Government confiscated the property of Robert E. Lee. The Commonwealth of Virginia passed the land to the United States Government with the Residence Act of 1790, approving a new capital city to be located on the Potomac River. The site was selected by President George Washington.

Indexes to Wills and Estates

- Wills 1800 to 1954 : A-E | F-L | Lee-Rankin | Ross-Z

- Will Book 9, 1868 to 1878

Images of Wills and Estates, Book 9, 1858 to 1878

Bacon, Ebenezer | Baggott, John | Ball, Horatio | Bartlett, John | Birch, William | Blow, William D. | Boothe, William J. | Boston, Richard C. | Bowden, Alexander | Brooks, John | Buckingham, William

Carlin, Moseley | Callendar, Margaret | Cartwright, Rachael | Cavenove, Louis | Chapman, George | Close, James T. | Close, S. J. | Constable, Mary | Cook, Henry | Corkett, Virgil | Crocker, F. P. | Crocker, S. W. | Cross, R. Y. | Cross, Sarah W.

Daingerfield, Reverly Johnson | Daingerfield, Henry | Dorsey, H. Carter

Fawcett, Joseph | Febrey, Nicholas | Fineacy, James | Flann, orphans | Fowle, Eliza F. | Fowle, William H.

Gardner, Eliza | Green, Mary | Gregory, Charles | Griffith, Sally W. | Grigg, Joseph | Grimes, Frank E. | Grimes, Thomas E.

Hagan, John C. | Hamilton, Nannie | Harrison, Robert | Hart, Frederick William | Haus, J. M. | Herbert, Betsy | Herbert, Betsy and Kitty | Hilton, James | Hooe, Daniel F. | Hunter, Alexander

Jamieson, Maria | Janney, Phineas | Johnson, Charles F. M. | Johnson, John T.

Lackey, Lula | Leadbeater, Mary | Lewis, John A. | Lloyd, Frederick | Lloyd, John J. | Lloyd, Richard

Manderville, Mary | Massie, Mary | McEwen, Thomas | Millburn, Benedict | Milburn, orphans | Millburn, orphans | Mills, William | Moore, Julius

Pearce, Allan | Peverill, George | Phillips, James B. | Presstman, Stephen Wilson

Quisenberry, Edith | Quisenbury, William

Ramsay, Eliza | Reid, James H. | Richards, William B. | Rigg, Townly | Roberts, Edward | Rotchford, Philip | Russell, Moses

Sackey, Seila | Samour, John W. | Smith, Alfred A. | Smith, Hugh C. | Smith, Robert | Smoot, Charles C. | Smoot, George H. | Southern, Richard | Stone, Charles S. | Swann, Mary M.

Thornton, William

Westman, Frank F. | Wheat, Robert W. | Whiting, Louisa | Whittesay, S. | Wibirt, Isaac | Willis, Michael | Wood, John | Wrenn, Philip

Young, Cornelius

Questions Must be Answered

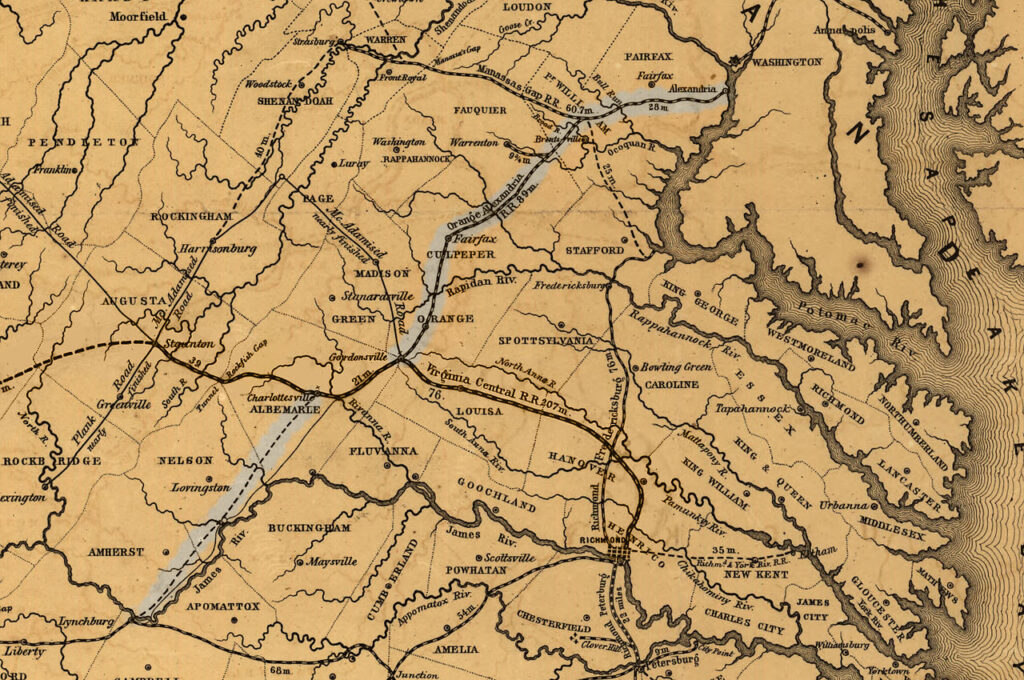

Daniel Hooe is Enriched by his Timely Investment in the Orange and Alexandria Roadroad

A Few Suggestions to Help Find Difficult Ancestors

Everyday Life in Colonial Days