- Hours: 10:00 am - 10.00 pm

- Inquiries

In England, the price of butter fluctuated very much during the 17th century. Between 1643 and 1652 it was very dear, then declined for 30 years, then rose in price again until the last decade. In 1600, it commanded five pence and one-seventh of a penny a pound. By the end of the century, it had sunk to still lower figures. The Virginia colonists drank as much cider as did beer. Of course, beer was consumed because the water was impure in England and it was thought that beer was wholesome. Large quantities of cider were frequently the subject of specialities. Peter Marsh of York County (about 1675) entered into a bond to pay James Minge 120 gallons. Cider was also used as payment for rent. Alexander Moore of York County upon his decease bequeathed 20 gallons of raw cider and 100 and 3 of boiled. Richard Moore of the same county kept on hand as many as 14 cider casks. Richard Bennett made about 20 butts of cider annually, while Richard Kinsman compressed from pears growing in his orchard 40 or 50 of perry. These liquors seemed to have been kept in butts, hogsheads and runlets. A great quantity of peach and apple brandy was also manufactured.The Assembly of 1623-1624 recommended to all new comers that they should bring in a supply of malt to be used in brewing liquor, thus making it unnecessary to drink the water of Virginia until the body had become hardened to the climate. Previous to 1625, two brew-houses were in operation in the colony, and the patronage which they received was very liberal.

Barley and Indian corn were planted to secure material for brewing. Cider was used as common as beer and in season it was found in the home of every planter. Wild fowls were plentiful in rivers, creeks and bays, and were so numerous in autumn and winter that they were regarded as the least expensive food on the table of the planter. There were large flocks of wild turkeys. The goose, mallard and the canvas-back, the red-head, the plover, and other species of the most highly flavored marine birds were more frequently cooked in the kitchen than domestic poultry. Sheepshead, shad, breme, perch, soles, bass, chub and pike swarmed in the nearest rivers. Source: Records of York County, vol. 1675-1684, p. 63.

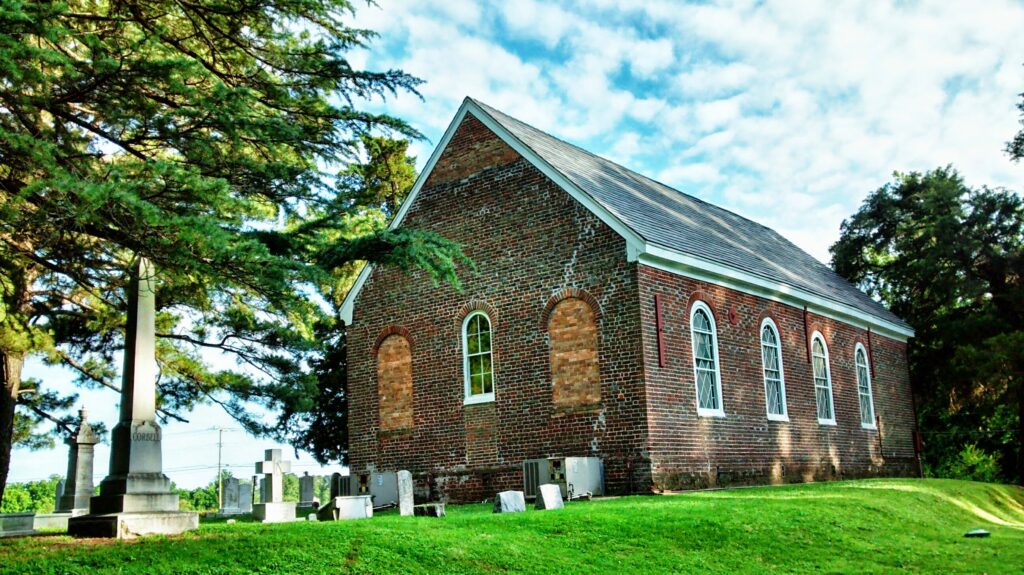

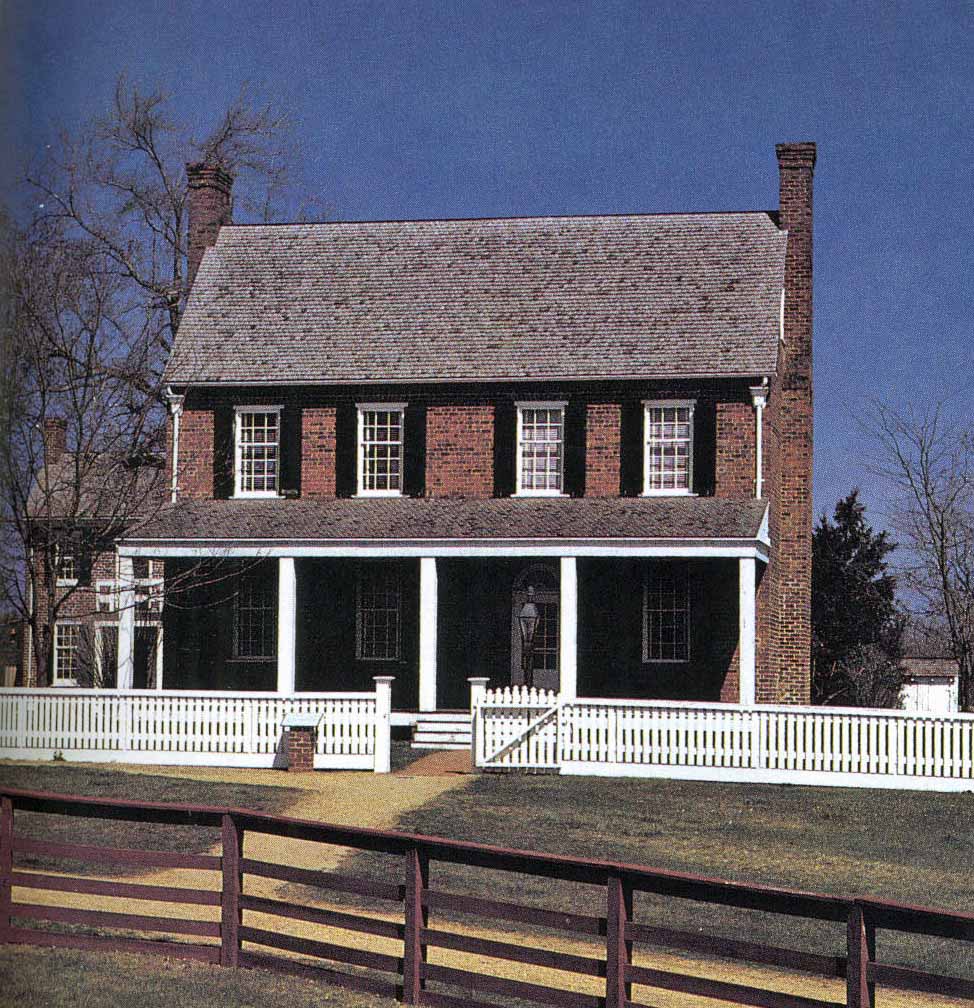

It was said by a Quaker witness in Northampton County that “the ministers who came into this country were raveninge wolves and hungry dogges and would preach no longer than they were fed.” Rev. Robert Powes of Lower Norfolk County in 1652 owned 64 volumes of books. For four years Powes performed all of the ministerial duties of Lower Norfolk County and received no compensation. In 1648 the vestry paid him one years full tithe in tobacco and corn. An inventory taken in 1652 disclosed that he was the owner of no inconsiderable aount of property, however, his personalty was valued at nearly 12,000 pds of tobacco and included a large quantity of household furniture and utensils, 18 head of cattle and seven head of swine. He also possessed a boat. He instructed in his will that the cattle should pass to his daughter who was living in the Mother Country (England). To his only son, Robert, he devised the remainder of his estate. Hence, the life of clergymen in the Virginia Colony was a sparse existence at most, depending upon the parishers for support, even food. The churches were comprised of a vestry, who created boundaries, measured roads, visited parishioners, and a number of charitable duties. Attendance to the Anglican Church was required, as well as tithing which was usually done in the form of tobacco.